Nominal Roll of Australian Veterans of the Korean War

Help

Close HelpSearch

The Nominal Roll of Australian Veterans of the Korean War honours and commemorates over 18,000 veterans who served in Australia's defence forces during the period 27 June 1950 to 19 April 1956 either in Korea or in the waters adjacent to Korea.

The Nominal Roll is an index of information that provides a 'snapshot' of individual service gathered from service records.

You can search for an individual's Korean War service details, print a commemorative certificate, provide feedback, and print a permission letter to use a service badge for commemorative purposes.

Other sites you may be interested in:

History

Origins of the Korean War, 1945-1950

The conflict arose out of the ashes of the Second World War amid Allied attempts to cooperate in the dismantling and disarmament of the Japanese empire. Unfortunately, in the case of Korea, these attempts were overtaken by the newly emerging Cold War between the West and the Communist Bloc. Korea, which had been annexed by Japan in 1910, contained a large Japanese garrison and colonial administration which needed to be demobilised and repatriated. To oversee this process Soviet forces moved into the north of the country in late August 1945 and American forces landed in the south two weeks later. Both nations agreed to use the 38th parallel as the dividing line separating their two zones of occupation.

Hopes for a smooth transition to an independent and unified Korea soon faded as Cold War tensions prevented the Soviets and Americans from agreeing on the manner by which this was to be achieved. The problem was then passed on to the newly-formed United Nations to try and resolve. In November 1947 the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) was formed to oversee elections for a constituent assembly aimed at unifying the country and allowing the withdrawal of the American and Soviet occupation forces. However the Soviets refused to hold elections and did not allow UNTCOK into their zone. Despite this the Americans went ahead with the election in the south, which was won by a coalition of nationalist parties under the leadership of Syngman Rhee. This government in the south was recognised by the United Nations as the Republic of Korea (ROK) in October 1948. In the meantime the Soviets established a Communist regime - the Democratic People's Republic of Korea - in the north under the leadership of Kim Il Sung. Thus the 'temporary' division along the 38th parallel hardened into a de facto frontier between the two rival Korean governments.

Initially Kim Il Sung tried to overthrow Rhee's government by waging a guerrilla war against the south. However the Communist insurgency failed to take hold and by 1949 Kim began to lobby his Soviet backers for permission to launch a conventional military invasion of South Korea. At first the Soviets withheld their support for such a venture as they did not wish to become embroiled in a war against the United States over Korea. However within the space of 12 months Moscow reversed this decision and gave Kim the approval he sought. This change of heart was due to a number of factors: Mao Zedong's October 1949 victory in the Chinese Civil War had greatly strengthened the power of the Communist Bloc throughout Asia; the Soviets had successfully tested their first atomic bomb in September and could now respond to the Western nuclear threat in kind; and finally, a number of ambiguous diplomatic statements by the Americans, coupled with the withdrawal of the last of their occupation troops, had given the impression that the United States no longer considered Korea to be an area of strategic importance.

The North Korean Invasion and the International Response, June-July 1950

Kim assured the Soviets that the North Korean People's Army (NKPA) would be able to overrun the South in a short war and unify Korea under Communist rule. The NKPA could muster approximately 230,000 troops, a large proportion of whom were veterans of the Chinese Civil War, and was well equipped with Soviet-made tanks, artillery and aircraft. By comparison the ROK army was only 100,000 strong, lightly-armed, and for the most part poorly trained. Thus Kim had every reason to feel confident of success and initially everything went according to plan for the North Koreans. The invasion began on 25 June 1950 and within three days NKPA troops had captured Seoul, the South Korean capital. While some ROK units quickly collapsed, others fought bravely but still failed to halt the NKPA onslaught. With no anti-tank weapons to speak of, South Korean soldiers had no answer to the North Korean tanks, which wreaked havoc wherever they were encountered.

However the North Koreans and the Soviets had misjudged the American reaction to the invasion. Within 24 hours of the North Korean attack President Harry S. Truman decided that the United States would intervene militarily on the side of South Korea. On 29 June General Douglas MacArthur, the American commander of the Allied occupation forces in Japan, was ordered to commit American air and naval forces under his command to the defence of South Korea. At the same time the United States succeeded in having the UN Security Council condemn the invasion and call for a North Korean withdrawal. When this demand was ignored the Council passed a resolution on 7 July authorising the establishment of a "United Nations Command" (UNC) in South Korea under American leadership. By the war's end a total of 21 countries, including Australia, had contributed military and medical contingents to the UNC although most of its strength came from the United States and South Korea.

Battle of the Pusan Perimeter, August-September 1950

Despite these developments the NKPA continued its advance deep into South Korea. The first American ground units to reach Korea had been hurriedly dispatched from occupation duties in Japan and lacked their full complement of men, heavy weapons and other equipment. These advance units of the US Eighth Army suffered a number of defeats at the hands of the NKPA before they finally succeeded in establishing a defensive line centred around the South Korean port city of Pusan. The North Koreans mounted a series of increasingly desperate offensives to wipe out this last remaining enclave of UNC resistance but failed to achieve a decisive breakthrough. The Battle of the Pusan Perimeter raged throughout August and into early September taking a heavy toll in lives on both sides. But while the NKPA struggled to replace the losses in men and equipment, the UNC forces were actually increasing in strength as a major international military build-up took place in both Pusan and nearby Japan.

Inchon and the UN Counter-Offensive, September 1950

By the middle of September General MacArthur, now Commander-in-Chief, UNC, was ready to launch a dramatic counter-attack. On 15 September the US X Corps, spearheaded by the 1st US Marine Division, made a daring amphibious landing at Inchon, a port on Korea's west coast that was barely 20 kilometres away from Seoul. Within two days the Americans had fought their way to the outskirts of the capital. Meanwhile, some 300 kilometres to the south-east, the UNC forces at Pusan also went over to the attack and broke through the encircling ring of NKPA forces on 23 September. Three days later UNC units spearheading the break-out from Pusan linked up with American troops driving south from Inchon, while Seoul finally fell to the Americans on 27 September.

This dramatic turn of events left the NKPA in complete disarray. The bulk of the NKPA's strength had been concentrated around the Pusan Perimeter and now these troops had either been cut off and surrounded or forced into a head-long retreat northwards. By the beginning of October the NKPA had lost approximately 150,000 men and most of its heavy weapons and equipment. By the time the last of its survivors had escaped across the 38th parallel the NKPA had been virtually annihilated as a cohesive fighting force.

The Chinese Military Intervention, October 1950

Encouraged by the overwhelming magnitude of the UNC victory the Americans now pressed for, and won, UN approval to continue the advance past the 38th parallel and into North Korea. The North Korean capital, Pyongyang, was captured by UNC troops on 19 October. However these moves were extremely provocative to the People's Republic of China which feared the creation of a unified pro-Western Korea on its doorstep. Beijing issued veiled warnings that it would be forced to intervene militarily if the UN forces kept on heading towards the Yalu River, which formed the boundary between China and North Korea. Now it was the turn of the United States and its supporters to misjudge their opponent's intentions. MacArthur convinced Truman that the Chinese were bluffing and continued to drive his troops on towards the Yalu.

Even when advance parties of Chinese soldiers were encountered by UNC forces towards the end of October MacArthur dismissed their significance and insisted that his troops press on. On 25 November the Chinese finally struck in force and the UNC suddenly found itself under attack from 300,000 Chinese soldiers under the command of General Peng Dehuai. Officially referred to as the "Chinese People's Volunteers" (CPV) by Beijing the Chinese troops were in fact regular soldiers and, for the most part, experienced combat veterans. The CPV designation was simply a device by which the People's Republic of China could officially deny that it was directly involved in the conflict.

The UNC Retreat, November 1950 - January 1951

The UNC forces were ill-prepared for the Chinese offensive and many units were overrun and destroyed while the rest were forced into a nightmarish retreat, under harsh winter conditions, all the way back to the 38th parallel. Pyongyang was abandoned by the retreating UNC troops on 5 December. The Chinese kept up the pressure by mounting another major offensive on 31 December, which forced the UNC to evacuate Seoul and Inchon and fall back below the 38th parallel to new defensive positions along the Han River. There the UNC forces were finally able to regroup and make a stand. In February the Chinese launched their "Fourth Phase Offensive" and attacked this line but failed to break through and were repulsed with heavy losses.

The Soviet Military Intervention, November 1950

At the same time as Chinese troops intervened in strength on the ground UNC pilots and other aircrew suddenly found themselves being attacked by MiG-15 fighter jets. The total dominance of the air that the UNC had achieved came to an abrupt end with the appearance of these state-of-the-art Soviet-built jets. Publicly these aircraft were said to be flown by Chinese pilots but in fact many of them were flown by Soviet pilots. Stalin had promised Mao Zedong that the Soviet Union would help the Chinese to establish a modern air force capable of challenging the American, South Korean, Australian and other UNC air forces over Korea. As part of this promise Stalin also agreed to send Soviet pilots and ground crews to operate the jets until enough Chinese could be trained to replace them. The Soviet 64th Aviation Corps was deployed to Chinese air bases in nearby Manchuria in November 1950 and, in all, approximately 72,000 Soviet air force personnel passed through this formation before it was withdrawn in 1953. The Soviets always officially denied having any direct involvement in the Korean War and it was only in the early 1990s, after the end of the Cold War, that Russia finally admitted its part in the conflict. Although it did not take long before UNC aircrew began to report hearing Russian being spoken during their encounters with the MiGs, the United States and other UNC governments also denied any Soviet involvement at the time. This was because they feared that revealing the presence of Soviet pilots to the public would lead to political pressure for direct retaliation against the Soviet Union and thus risk a further escalation of the war.

The UNC Regroups, February - March 1951

The UNC forces then undertook a series of offensives of their own and by early April they had recaptured Seoul and driven the Chinese back across the 38th Parallel. Unlike the earlier UNC offensives these attacks were strictly limited in their objectives and there was no thought of trying to repeat the dramatic thrusts of the previous year. By this stage the United States and the other nations of the UNC had given up any ambitions to unify Korea, and were now simply fighting to protect the territorial integrity of South Korea. When General MacArthur publicly questioned this decision, and instead argued for an escalation of the war to include attacks on the Chinese mainland, he was relieved of his command by President Truman and replaced by another American, General Mathew Ridgeway.

The Chinese "Fifth Phase Offensive", April - May 1951

The Chinese however still hoped to conquer South Korea and win an outright victory. On 22 April the full weight of the Chinese 9th Army Group fell upon the 6th ROK Division at Panam-ni while the 29th British Brigade, holding positions along the Imjin River, found itself under attack by the Chinese 19th Army Group. These attacks marked the beginning of the Chinese "Fifth Phase Offensive" and represented the two prongs of a pincer movement designed to encircle and cut off the bulk of UNC forces in the western half of Korea. The Chinese smashed through the 6th ROK Division but were then decisively delayed in a desperate holding action mounted by the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment and the rest of the 27th Commonwealth Brigade around Kapyong. A similar rearguard action was also carried out by the 29th British Brigade on the Imjin, and the efforts of these two brigades allowed the rest of the UNC forces to escape the Chinese trap. After a further week of bitter fighting the UNC forces were able to re-establish a new defensive line just in front of Seoul.

Despite failing to achieve a decisive breakthrough in the west the Chinese now switched the focus of their efforts on to the eastern half of the front. On 16 May the 9th and 3rd Chinese Army Groups, supported by units of the re-constituted NKPA, attacked the 3rd ROK Corps and quickly overwhelmed it. However the Chinese once again failed to achieve a decisive breakthrough and on 21 May the UNC forces counter-attacked across the entire front. The Chinese troops, already exhausted by their own offensives over the previous two months, were unable to withstand the UNC assaults and the Communist defences soon began to crumble. Attempts by the Chinese and North Koreans to organise an orderly retreat to new positions soon degenerated into a total rout as the superior mobility of the UNC forces saw them outflank and surround their Communist opponents, while UNC fighter-bombers pounded the Chinese and NKPA troops from the air. For the first time large numbers of Chinese prisoners of war were taken by UNC forces, and for a moment the Chinese and North Korean armies in Korea teetered on the brink of total collapse.

Cease-Fire Negotiations Begin, July 1951

The Chinese and North Koreans were saved, at least in part, by the deliberate decision of the UNC commander, General Ridgeway, not to try and pursue them all the way to the Yalu River. Instead the UNC forces were content to stop short of Pyongyang and establish a new frontline on the northern side of the 38th parallel. This was in line with the policy of limited war adopted by the UNC nations earlier that year. The Chinese, after launching five major offensives to no lasting effect, were also now ready to abandon the goal of outright victory in Korea. Accordingly both sides agreed to enter into formal armistice negotiations and these talks began on 10 July at the North Korean town of Kaesong, before shifting to another North Korean site, Panmunjom, in October.

Stalemate: The War of Attrition, July 1951 - July 1953

Unfortunately the negotiations would drag on for another two years before an agreement could be reached. Major sticking points included the final position of the cease-fire line and the repatriation of prisoners of war. Meanwhile the fighting continued, as both sides engaged in a war of attrition aimed at wearing the other down and thus improving their respective bargaining positions at the armistice negotiations. This last, and longest, phase of the conflict bore a striking resemblance to the trench warfare of the First World War. Although further offensives were undertaken by the Chinese and UNC forces during this period, they were usually limited attacks designed to capture a specific local objective, such as a town or hill. Often their only purpose was to lure the opposite side into counter-attacking in an attempt to inflict maximum casualties on them. The Chinese thought that such a strategy of attrition would favour them because of the superior numbers of men they could call upon: The UNC forces thought that attrition favoured them because of the superior firepower they could bring to bear upon the battlefield. The result was a series of hard-fought battles where a piece of ground could change hands anywhere up to a dozen times. A succession of local features known only to UNC troops by names like "Heartbreak Ridge", "Pork Chop Hill" and "The Hook" became bywords for brutal combat.

The Armistice, 27 July 1953

By the time the negotiations were finally concluded and the Armistice came into effect on 27 July 1953 total military and civilian casualties for all sides involved in the conflict were approaching five million. Prisoners of war were exchanged between 5 August and 6 September and all parties agreed to attend a peace conference in Geneva in April the following year. However this conference failed to produce a peace treaty and therefore, although the cease-fire brought about by the Armistice has remained in effect since then, technically speaking the Korean War has never officially ended.

Tensions remained high throughout the rest of the 1950s and both sides initially retained large forces in Korea in case hostilities resumed. Nonetheless by 1957 most of the nations of the UNC, including Australia, had withdrawn the last of their military contingents from South Korea while the last Chinese combat units left North Korea the following year. In the meantime the United States and South Korea had signed a Mutual Defence Treaty under which the US Eighth Army remained in the country to act as a deterrent against any possible future aggression against the South.

Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy contributed warships to the Korean War from the very early days until the signing of the armistice, and beyond after the armistice came into effect.

At the start of the war the frigate HMAS Shoalhaven was already on station in Kure, Japan, as part of Australia's contribution to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) when UN Security Council Resolution 83, calling on member states to assist South Korea in defending itself, was passed on 27 June 1950. Two days later the Australian Government placed the Shoalhaven and its intended relief, the destroyer HMAS Bataan, which had also arrived in the area, at the disposal of General Douglas McArthur, Supreme Commander Allied Powers, Japan. Both ships were immediately ordered to join elements of the British Far East Fleet: on 1 July Shoalhaven commenced convoy escort duties between the ports of Sasebo, Japan, and Pusan, South Korea, while Bataan joined a task group charged with imposing a naval blockade on South Korea's west coast. The involvement of these two ships heralded the beginning of a strong Australian naval contribution to the conflict.

Control of the seas around the Korean peninsula by United Nations Command (UNC) naval forces helped to save South Korea from total defeat in the first weeks of the war. UNC warships, mostly drawn from the United States Navy's Seventh Fleet, were able to blockade the peninsula, land raiding parties, supply or rescue isolated groups of South Korean and American troops, support ground operations with bombardments of coastal targets, and send in air strikes from aircraft carriers. The Royal Australian Navy assisted in all of these operational tasks.

For the duration of the Korean War, the Royal Australian Navy always maintained at least two destroyers or frigates on station off the Korean peninsula. Some Australians also served on exchange in British warships. In August 1950 the destroyer HMAS Warramunga relieved Shoalhaven - the latter had already spent five months in Japanese waters prior to the outbreak of the war and was overdue to return to Australia for a refit. Warramunga began its tour as part of the destroyer screen for the British aircraft carrier HMS Triumph before embarking on a series of close inshore patrols of the Korean west coast. In the course of these patrols Warramunga played a supporting role in the daring American amphibious landings at Inchon in September 1950.

Two months after the Inchon landings, when the Chinese entered the war and the United Nations Command was again forced to retreat, Warramunga and Bataan provided close inshore support for the retreating UNC forces. During December 1950, the Australian ships took part in the evacuation of Chinnampo and Inchon, taking off troops and refugees and participating in naval bombardments of the encroaching Chinese and North Korean forces. This period featured intensive operations for many of the United Nations Command warships - during February 1951, Warramunga spent only five days out of the operational area, steamed nearly 5000 nautical miles (9250 kilometres) and fired more than 1000 rounds against shore targets.

In May 1951, the frigate HMAS Murchison replaced Bataan, one of the original warships on station. It was soon in action, and from July took part in UNC operations on the Han River estuary, a forty mile stretch of mud banks and islands bisected by a bewildering maze of channels, only a few of which were navigable, running to the sea. This was a particularly hazardous assignment as the whole area was under Communist control, and any ship that ventured up one of the channels risked being shelled by Communist shore batteries. On 28 September the Murchison became engaged in a heavy fire-fight with the Communist gunners. The Australian warship was hit numerous times and was lucky to emerge from the episode with only one rating wounded.

The following month the tempo of Australian naval operations in the Korean War increased dramatically when the aircraft carrier HMAS Sydney was deployed to the area. It carried three Naval Air Squadrons - Nos 805 and 808 Squadrons, equipped with Hawker Sea Fury fighters, and No. 817 Squadron, equipped with Fairey Firefly fighter-bombers. In its first combat tour Sydney completed a total of seven operational patrols off the west coast of Korea before returning to Australia in February 1952. During that time the Naval Air Squadrons flew a total of 2,366 sorties - mostly combat air patrols and ground attack missions - under incredibly trying conditions. Sydney was struck by a typhoon during the aircraft carrier's first patrol and then, in the latter half of its tour, had to contend with winter storms that covered the flight deck and the aircraft in snow and ice. Typhoon 'Ruth' produced 70 knot (130 kilometre per hour) winds and 45-foot (13.7 metre) waves that washed one Firefly overboard, caused the 15,700 ton carrier to roll 22 degrees at one point and gave the ship's company a severe battering. Natural disasters aside, three pilots, all from 805 Squadron, were killed and a total of 16 aircraft (excluding Typhoon Ruth's victim) were lost on operations in the course of Sydney's first Korean tour.

Other Australian warships to see active service during the war were the destroyers HMA Ships Tobruk and Anzac and frigates HMA Ships Condamine and Culgoa. They too served in the demanding role of maintaining the United Nations Command naval blockade, serving in carrier screens and bombarding shore targets. As with Sydney and their other predecessors the crews of these ships were often tested by the foul and, in winter, freezing cold weather for which the waters around the Korean peninsula were renowned. Bataan and the Warramunga both returned to complete a second operational tour in 1952, a feat emulated by HMAS Anzac which completed its second tour a month before the Armistice was signed in July 1953. However the end of hostilities did not immediately signal the end of the Royal Australian Navy's involvement in Korea.

Australia continued to send ships to serve in Korean waters with the United Nations Command for another two years after the Armistice. HMA Ships Tobruk, Murchison, Shoalhaven and Condamine all returned to complete their second tours between 1953 and 1955. HMAS Sydney also returned for a second time in November 1953 with a new carrier air group embarked. No. 805 Squadron remained aboard but Nos. 808 and 817 Squadrons had been replaced with Nos. 850 and 816 Squadrons respectively. In addition to these 'old hands' the destroyer HMAS Arunta added its name to the roster of ships of the Royal Australian Navy to serve in Korea when it joined the UNC for an eight-month tour in February 1954. By the end of 1954 Australia, in conjunction with other British Commonwealth countries who had contributed forces to the UNC, began to implement a phased withdrawal of its forces from Korea. When HMAS Shoalhaven returned to Australia in March 1955 it was not replaced and HMAS Condamine was left to complete its tour as the sole Australian ship in the UNC. Indeed, Condamine was the last Australian ship to serve in the UNC and its return to Australia in November 1955 signalled the end of Australia's naval involvement in Korea.

Australian Army

On 27 July 1950 Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced that, in addition to the air and naval forces already committed, Australia would raise a contingent of ground troops for service in the Korean War. The Australian Government decided that the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR), which was then stationed in Japan as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF), would form the nucleus of this contingent. Australia had in fact been in the process of reducing its commitment to BCOF immediately prior to the outbreak of the conflict in Korea, and as a result of this 3 RAR did not possess a full complement of men when Menzies made his announcement. In an effort to bring 3 RAR up to strength and provide a pool of reinforcements for it, the Government initially sought to recruit 1000 volunteers for service in Korea. Under the terms of their enlistment these 'K' Force volunteers had to be between 20 and 40 years of age, possess prior full-time military experience, and be prepared to serve for a total of three years overseas.

Recruitment for K Force began on 21 August 1950 and so overwhelming was the response that for every man chosen by the Australian Army another three had their applications to join rejected. The result was that, in addition to possessing prior military experience, most of the volunteers selected were Second World War veterans with extensive combat experience. This experience meant that the need for basic training could be dispensed with and instead the men were quickly dispatched to Japan to undergo a short, but intensive, course of refresher training before joining 3 RAR in Korea. Indeed, the first groups of K Force volunteers were flown to Japan in time to join the battalion before it embarked for South Korea aboard an American troopship, Aitken Victory, on 27 September.

Upon landing at Pusan the following day, 3 RAR, reinforced with volunteers from other units of the Australian Regular Army as well as the first batch of K Force men, found that it had arrived in the midst of MacArthur's bold counter-offensive against the North Koreans. The Australians were ordered to move north where they joined two British battalions in the pursuit of the retreating North Korean People's Army (NKPA), forming the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade in the process. The brigade was airlifted to Kimpo airfield, near Seoul, in the first week of October and subsequently moved to Kaesong, where it came under the command of the United States Army's 1st Cavalry Division. The United Nations Command (UNC) resumed its advance into North Korea a few days later and 3 RAR suffered its first battle casualties on 13 October during operations to clear a pocket of enemy troops trapped around the village of Kumchon, 16 kilometres north of Kaesong. The 27th British Commonwealth Brigade, with 3 RAR often in the lead, then spent the next two weeks fighting its way north during the United States Eighth Army's drive on Pyongyang and beyond.

The 27th British Commonwealth Brigade captured the town of Chongju on 29 October and this marked the northernmost point of Korea reached by Australian troops during the conflict. Within a week however 3 RAR, along with the rest of the brigade, found themselves being ordered to fall back to positions to the south, as the first major Chinese offensive of the war took the extended UNC forces by surprise. For the next two months the Australians were caught up in a series of staged withdrawals as the UNC struggled to regroup and re-establish a solid defensive line against the Chinese attacks. In addition to dealing with a relentless and powerful new enemy the Australian soldiers also had to endure the bitter privations of their first Korean winter. Temperatures as low as minus 27 degrees celsius were recorded and, despite being issued with American winter uniforms, frostbite, hypothermia and other exposure-related illnesses began to appear amongst the men.

When the UNC finally established a new defensive line in January the Australians held a sector of the front for three weeks, before going into reserve at the end of the month. This respite was short-lived for within a week the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade had been ordered back into the line to support the UNC counter-offensive launched at the start of February. The Australians carried out mopping up actions around the Yoju area until the Fourth Phase Chinese offensive forced the UNC to go back onto the defensive. Once the Chinese attack had been halted the UNC forces resumed their methodical, albeit limited, series of advances throughout March and April. As part of these operations 3 RAR fought in a number of actions - Hill 614, Hill 410, the Chojong Valley and others - as the UNC clawed its way back across the 38th parallel.

However the Chinese still harboured hopes for an outright victory in Korea, and on 22 April they launched the Fifth Phase Offensive. Designed to cut off and destroy the bulk of the United States Eighth Army, the massive Chinese assault almost succeeded. They were thwarted by two desperate rearguard actions by British Commonwealth troops. One was carried out by the 29th British Brigade in the Battle of the Imjin and the other was waged by 3 RAR and the rest of the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade in the Battle of Kapyong. For two days the Australian battalion delayed the Chinese advance in a desperate struggle that cost the Australians 83 casualties but which allowed the bulk of the UNC forces to escape the Chinese trap. For its part in the Battle of Kapyong, 3 RAR was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation by the United States.

In the aftermath of Kapyong and the defeat of the Chinese Fifth Phase Offensive a major reorganisation of British Commonwealth forces in Korea took place. The 27th British Commonwealth Brigade Headquarters was replaced by the 28th British Commonwealth Brigade Headquarters, and 3 RAR was transferred to the new brigade. In turn the expansion of Canada's contribution from a single battalion to an entire brigade - the 25th Canadian Brigade - in May led to the formation of the 1st British Commonwealth Division on 28 July 1951. Apart from the Australians the Commonwealth Division included troops from the United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand, and India. Although the Australian infantry battalions assigned to the 28th Commonwealth Brigade would remain the focal point of Australia's contribution to the division, Australian contingents of various sizes could be found scattered throughout the various divisional units of the new formation from its headquarters to its field postal unit.

During that time the Australian infantrymen found themselves engaged in trench warfare eerily reminiscent of the sort experienced by their fathers' generation in the First World War: The Australians aggressively patrolled no man's land between the Communist positions and their own, and carried out raids on enemy trenches to capture prisoners and assert their dominance of the sector. Much of the rest of their time was spent on improving both their defences and their living conditions - trenches were gradually roofed in, bunkers reinforced and dug-outs made more comfortable. This routine was punctuated by the need to fend off large-scale Chinese attacks and carry out their own. In October 1951 3 RAR was tasked with capturing Hill 317, known locally as Maryang San, and the surrounding heights. 3 RAR succeeded in driving the Chinese from these positions in a gruelling five-day battle that cost the Australians 109 casualties (20 killed and 89 wounded). Fifty Chinese soldiers were taken prisoner and the bodies of a further 283 were found amongst the captured trenches and dug-outs. Thirty seven soldiers of 3 RAR were decorated or mentioned in dispatches for their actions during the battle. Other actions of note included 1 RAR's assault against Hill 227 in 1952 and 2 RAR's defence of 'The Hook' in July 1953.

To support these combat units the Australians set up their own forward base organisation in Korea, known by the somewhat ungainly title 'Australian Forces in Korea Maintenance Area' (AUSTFIKMA) in October 1950. AUSTFIKMA operated out of Pusan and its primary mission was to keep 3 RAR supplied with those items that could not be obtained from the Americans. In December AUSTFIKMA came under the operational command of the newly formed Headquarters, British Commonwealth Forces, Korea, (HQ, BCFK) and efforts were made to integrate the supply needs of the increasing number of British Commonwealth contingents arriving in Korea. By February 1951 congestion at Pusan, and the unsuitability of any other available South Korean port, led HQ, BCFK, to withdraw all British Commonwealth logistics units from Pusan and re-establish them as a unified Commonwealth Base organisation in Kure, Japan. For the rest of the war Australian Army logistics, medical and administrative personnel provided a substantial portion of the Commonwealth Base organisation and individuals were often dispatched to Korea on temporary duty.

Of particular note was the work of the British Commonwealth General Hospital at Kure which was responsible for treating most of the British Commonwealth casualties evacuated from Korea. Personnel from both the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps and the Royal Australian Army Medical Corps served with distinction at this facility. In addition to regularly taking part in medical evacuation flights from Korea to Japan, a small number of them also served in the British Commonwealth Communications Zone Medical Unit established in Seoul in September 1952. An Australian soldier (or airman) who was wounded, accidentally injured or who fell seriously ill would pass through a series of UNC medical field units before being evacuated to Iwakuni, Japan, and thence taken by train to the British Commonwealth General Hospital in Kure. Exceptions to this process were those patients with serious neurosurgical or chest wounds who were normally passed on to a specialist United States Army Hospital in Tokyo. Patients who were expected to recover to the extent that they could return to their units were, upon being discharged from hospital, usually placed in the 1st Australian Reinforcement Holding Unit, part of the British Commonwealth Base Organisation at Kure, until they were fit enough to return to Korea.

From late 1951 onwards all Australian Army personnel who had completed four months' service in Korea were entitled to five days' 'local leave' in Japan. In addition to this, those who had completed eight months' service in Korea were entitled to 20 days' local leave in Japan. Besides local leave the other reason a soldier might find himself being sent to Japan for a couple of weeks was if he was sent on a course run by the Commonwealth Division Battle School. Situated in Haramura, Japan, the Battle School was primarily designed to provide intensive combat training for reinforcement and replacement personnel prior to their deployment to Korea. Even so, a soldier already serving with a unit in Korea could sometimes be sent to attend one of the specialist courses offered by the School. These courses generally lasted between 4-6 weeks after which (barring accident or illness) the soldier returned directly to his unit in Korea.

The signing of the Armistice in July 1953 did not immediately lead to a withdrawal of the Australian infantry battalions and the base units that supported them. Tensions along the cease-fire line remained high and the Australian Government was encouraged to keep its forces in Korea for as long as possible. However of the three services the Australian Army faced the hardest struggle to maintain its forces in Korea. The K Force recruitment program, which had been expanded in the wake of Australia's commitment to deploying two battalions to the conflict, lost nearly all of its appeal with the signing of the Armistice and the Army reported a sharp drop in recruits as a result. Under such circumstances it quickly became apparent that Australia would not be able to sustain two battalions in Korea in peacetime. Accordingly 3 RAR was withdrawn in November 1954 and not replaced. In the meantime 2 RAR completed its first tour on 2 April 1954 when it was relieved by 1 RAR. The sole Australian battalion in the UNC was finally withdrawn on 24 March 1956 when an under-strength 1 RAR embarked at the port of Inchon for Australia. That month the remaining British Commonwealth personnel were grouped together in a formation known as the 'Commonwealth Contingent, Korea', which included a small group of Australian Army signallers.

Royal Australian Air Force

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) began its involvement in the Korean War just one week after the invasion of South Korea. On 2 July 1950, No. 77 (Fighter) Squadron RAAF, based in Iwakuni, Japan, as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force, flew its Mustang fighters into combat for the first time as a unit of the United Nations Command.

No. 77 Squadron was the only RAAF combat squadron committed to Korea by the Australian Government, and it remained on active service there until the end of the war. Initially the Australians were tasked with escorting American bombers to and from their targets as well as carrying out low-level air strikes of their own. The latter involved attacking bridges, railway lines and other targets in an attempt to disrupt and slow down the North Korean advance. The Mustang fighters, with which the squadron had been equipped since the end of the Second World War, were easily adapted to the ground attack role in Korea. Capable of operating from rough airstrips in the forward area, these aircraft were heavily armed with six 0.5-inch calibre machine-guns and either six high-explosive rockets or two 227-kilogram bombs slung under the wings. At the height of the desperate American and South Korean defence of the Pusan Perimeter, the Australian pilots, although still officially based in Japan, would often operate their Mustangs from a forward airstrip at Taegu, inside the Perimeter, flying anything up to six combat missions in a day.

The Australians quickly developed a reputation for excellence in the ground attack role but this recognition came at a heavy price. While the North Korean air force was soon driven from the sky, Communist ground-based anti-aircraft defences continued to pose a formidable threat to all UNC aircrews, but those engaged in ground attack missions were particularly vulnerable as they had to fly at low levels to hit their targets. Less than a week after beginning operations, No. 77 Squadron suffered its first combat fatality of the war when Squadron Leader Graham Strout, a flight commander, was shot down by North Korean ground fire during an air -strike on the Samchok rail yards. Casualties mounted over the following months, including on 9 September 1950 the popular squadron commander, Wing Commander Lou Spence.

That same month, as the UNC launched its dramatic counter-offensive towards the 38th Parallel, the American Fifth Air Force, of which No. 77 Squadron was a part, began moving its fighter units to re-captured bases on the Korean peninsula. The Australians henceforth operated primarily from airbases within South Korea for the rest of the war. The living conditions on these bases were very basic and air and ground crews alike had to endure searing heat in summer, and freezing temperatures in winter, with only canvas tents for shelter.

In October 1950, all RAAF units attached to the United Nations Command were grouped into the newly formed No. 91 (Composite) Wing. In addition to No. 77 Squadron, the Wing included No. 491 (Maintenance) Squadron, No. 391 (Base) Squadron and No. 30 Communications Flight. A servicing section from No. 491 Squadron was attached to No. 77 Squadron in Korea to allow some major inspection and overhaul work on the aircraft to be undertaken in the field, and additional personnel were brought over from Japan on an ad hoc basis to assist in this work when required. Personnel from No. 391 Squadron were also sometimes detached for temporary duty with No. 77 Squadron.

No. 30 Communications Flight, redesignated No. 30 Transport Unit shortly thereafter, was equipped with Douglas Dakota transport aircraft and provided a vital link between No. 77 Squadron in Korea and the rest of No. 91 (Composite) Wing, which remained based in Japan. The aircrews of No. 30 Transport Unit made regular flights into South Korea, carrying troops and supplies in and evacuating wounded, injured and sick Australian and other British Commonwealth personnel on the return journey. Nursing sisters of the RAAF Nursing Service accompanied the aircrews on the aero-medical evacuation flights. On 7 March 1953 No. 30 Transport Unit had its status upgraded to that of a full squadron and was reconstituted as No. 36 (Transport) Squadron.

In April 1951 No. 77 Squadron was temporarily withdrawn to Japan to be re-equipped with British-built Gloster Meteor jet fighters. Previously, only one or two pilots on exchange with the United States Air Force had flown jet combat missions in Korea. After an intense two-month conversion from the prop-driven Mustangs to the jet-powered Meteors the squadron returned to operational duties in Korea in July 1951. On its return the squadron was stationed at Kimpo air base, just outside Seoul, and would remain based there, alongside dozens of American and other UNC squadrons, until the end of the conflict. Initially the Australians hoped that the new jets would allow No. 77 Squadron to resume its classic fighter role, but the Meteors proved incapable of holding their own in 'dog fights' against the Chinese and Soviet MiG-15s.

As a consequence, in September 1951 No. 77 Squadron found itself forbidden to carry out fighter sweeps over North Korea and relegated to second-line air defence duties. Frustrated by these restrictions and aware that the newly-acquired Meteor would not be replaced any time soon, in December the RAAF decided to once again employ No. 77 Squadron in the ground attack role. This was something of a gamble as no other operator of the Meteor, including the Royal Air Force, had thought the aircraft was suited to this role. However the Meteor made up for its disappointing performance as a fighter by proving to be one of the best ground attack aircraft of the war. In addition to its four 20-mm cannons the Australians installed rails to carry eight high-explosive rockets under the Meteor's wings, and this gave it the ability to deliver devastating and concentrated salvoes of firepower against ground targets.

But once again casualties were high, with about one in four of No. 77 Squadron's pilots killed or captured by the time of the Armistice. At the end of the war, No. 77 Squadron had flown 18,872 sorties but lost 34 Australian pilots killed in battle or accidents and six prisoners of war, along with four British exchange pilots killed and one prisoner of war. In the aftermath of the Armistice No. 77 Squadron remained in Korea until October 1954 when it returned once more to Japan, before finally departing for Australia aboard the aircraft carrier HMAS Vengeance in November. No. 491 (Maintenance) Squadron was disbanded and its personnel sent home the following month. The rest of No. 91 (Composite) Wing did not follow until March 1955. However two of No. 36 (Transport) Squadron's Dakotas and their crews were left behind to form the RAAF Transport Flight Japan. This small RAAF unit maintained a regular service between Japan and Korea carrying people, mail and freight until it too was finally withdrawn to Australia in June 1956.

About the Nominal Roll of Australian Veterans of the Korean War

The Nominal Roll of Australian Veterans of the Korean War was created to honour and commemorate over 18,000 veterans who served in Australia's defence forces during the period 27 June 1950 to 19 April 1956, either in Korea or in the waters adjacent to Korea.

The Nominal Roll is an index of information that provides a 'snapshot' of individual service gathered from service records.

You can search for an individual's Korean War service details, print a commemorative certificate, provide us with feedback if you wish, and find information about using a service badge for commemorative purposes.

Who is included?

The Nominal Roll includes approximately 5,700 members of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), 10,800 from the Australian Army, and 1,400 members of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) who served in the Korean War operational area.

A small number of Australian civilians are also included on the Nominal Roll. They include canteen staff who served on RAN ships deployed to Korean waters during the conflict, and members of philanthropic organisations, such as the Red Cross and the Salvation Army, who provided various forms of support to Australian service personnel in Korea.

Who is not included?

Australians who enlisted with other Commonwealth or Allied Forces are not included in this Nominal Roll. Respective overseas countries hold the Korean service records for those Australians.

Where are service records held?

The National Archives of Australia holds many of the service records of those who served in Korea. Service records not available from the Archives are still located at the Department of Defence.

What if an individual doesn't want to be listed on the Nominal Roll?

Individuals were given an opportunity to have their service details excluded from the website prior to it being published. However, should a veteran still wish to exclude their details, they should contact the Nominal Rolls team.

If you are a relative or acting on behalf of a veteran, you will need to include in your letter documentary proof of your bona fides, such as an enduring power of attorney.

How was the roll compiled?

A preliminary Nominal Roll of Australian Veterans of the Korean War was released in paperback format in April 1999. This was followed by the publication of an updated commemorative version in April 2000. The data contained in these rolls was developed and maintained as a basis for a series of Korean War health studies.

The service eligibility of all those whose names appear on the website has been verified from the original service record held by the Department of Defence.

Additional information concerning those who died was obtained from the Office of Australian War Graves and the Australian War Memorial.

Accuracy of the data collection

Every effort has been made to ensure that the Nominal Roll is as accurate as possible. If you believe the information displayed on the website is incorrect please contact the Nominal Rolls team.

What service documents were used to source this information?

The following Service-specific documentation was used to source the information:

- Royal Australian Navy Record of Service Card

- Australian Army Discharge and Record of Service Forms

- Royal Australian Air Force Record of Service Forms

Was the information always available from these service documents for each individual?

No, typically one or more of these documents would be used to provide as much information as possible. However, in the absence of these preferred forms, other official documents may be used to gather supporting information.

Is the Nominal Roll finished?

The Nominal Roll has been reviewed a number of times during the conduct of the various health studies and there have been minimal changes in recent years. The Department of Veterans' Affairs will update the Roll whenever new information becomes available.

Acknowledgements

Research Sources

The details displayed on this website have been compiled from information supplied by the following organisations.

Navy Naval History Directorate Department of Defence Russell Offices CANBERRA ACT 2600

Army Army History Unit Department of Defence Russell Offices CANBERRA ACT 2600.

Air Force RAAF Historical Records Department of Defence Russell Offices CANBERRA ACT 2600

Australian War MemorialAustralian War MemorialGPO Box 345CANBERRA ACT 2601

Honours

The Honour data for individual service men and women was provided by the Australian War Memorial.

Australian War MemorialAustralian War MemorialGPO Box 345CANBERRA ACT 2601

Honour Images

Honour images, displayed on this website, were taken from the following publications:

The Year 2001 CalendarPublished jointly by the Department of Veterans' Affairs and the Australian War MemorialHonours:

- Companion of the Distinguished Service Order

- Distinguished Conduct Medal

- Distinguished Flying Cross

- Distinguished Flying Medal

- Distinguished Service Cross

- Distinguished Service Medal

- George Cross

- George Medal

- Military Cross

Medal Yearbook 2001Edited by James Mackay, John W Mussell and the Editorial Team of Medal NewsPublished by Token Publishing Ltd. Devon, UK.Honours:

- British Empire Medal

- Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Member of the Order of the British Empire

- Officer of the Order of the British Empire

- Royal Red Cross (2nd Class)

British Orders, Decorations and MedalsBy Donald Hall (in association with Christopher Wingate)Published by Balfour PublicationsPrinted by Photo Precision Ltd St, Ives Huntington, EnglandHonours:

- Air Force Cross

- Air Force Medal

- Royal Red Cross (1st Class)

Photographs

The following photographs were provided courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (AWM), Canberra.

[HOBJ0418]A RAN Commander (Cdr), probably V G Jerram, on board his ship HMAS Culgoa.

[LEEJ0499]Vice Admiral Sir John Collins, First Member of the Australian Naval Board and Chief of Naval Staff, is on a tour of inspection of Commonwealth naval forces in Japan and Korea. Here Vice Admiral Collins inspects ratings on HMAS Condamine during his visit to the ship in Japanese or Korean waters.

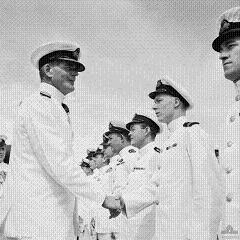

[HOBJ2406]Vice Admiral (Vice Adm) Sir Guy Russell, Commander in Chief Far East Station, shakes hands with an unidentified lieutenant standing beside other officers on board HMAS Sydney in Kure harbour, Japan. HMAS Sydney has replaced HMS Glory as the new flagship of Vice Adm Russell. The officer on the far right is possibly Lieutenant K W Shands.

[DUKJ3797]An unidentified anti aircraft spotter, probably on the RAN destroyer HMAS Bataan operating off the Korean coast pulls a thick duffle coat over his collection of jerseys and jumpers, and you can be sure he's wearing raw wool seaboot socks underneath his winter woollies and heavy serge trousers. A balaclava helmet gives some cover for the ears and cheeks, but stinging eyes and a numbed nose are always ills to be cured when the watch is ended.

[157648]Majon'ni, Korea. 1953-06-09. Unidentified men of C Company, 2nd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (2RAR), in the trenches of left forward Company position on The Hook after relieving 1st Battalion King's Regiment.

[DUKJ3958]Portrait of an unidentified pilot of 77 Squadron RAAF after returning from a combat mission in one of the unit's P51 Mustang fighter aircraft. He is wearing full flying uniform including survival gear, helmet, sidearm, oxygen mask and is carrying a satchel of maps.

[P03119_029] An informal portrait of 022222 Pilot Officer M J (Milt) Cottee serving with 77 Squadron RAAF in Korea. An original member of the Squadron at the outbreak of the war, he received a Mentioned in Despatches and a US Air Medal for his service as a P-51D Mustang pilot in 1950.

[P03119_025]An informal individual portrait of A4443 Sergeant K H (Kev) Foster DFM outfitted in his flying suit prepared for a sortie. He is a member of 77 Squadron RAAF serving in Korea. Standing in a lane between accommodation huts, his US manufactured flying equipment includes a helmet, goggles, oxygen mask, communications headset and various pouches. For his service between 1950-51 he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal.

[HOBJ2689]Flight Lieutenant (Flt Lt) John Harnetty, a Public Relations Officer with the Australian Army, who was seconded from the RAAF, stands beside his tent. Flt Lt Harnetty is wearing his officer's peaked cap with RAAF wings, scarf and leather gloves. He is visiting a camp in Korea during the beginning of the 1951 winter.

Data collected for the Korean War Nominal Roll

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

Name |

The individual's full name as recorded on the official record of service document. If the individual served under an alias, that information will also be displayed where known. Nicknames will not be displayed, as they are not recorded on the service record. If a woman married while enlisted, and the military authority amended the service record to her married surname, then that surname will be displayed. This approach has been taken so that the displayed surname aligns with the surname recorded on the paper service record. In such cases, a maiden name may not have been collected. |

Service |

Refers to one of the three services that form Australia's defence forces - Royal Australian Navy (RAN); Australian Army; Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). Where an individual served in more than one branch of Australia's defence forces, each period of service will be displayed as a separate record. To view all records for an individual, select 'ALL' in the Service box. |

Service Number |

The number allocated to the individual on enlistment into one of the three branches of Australia's defence forces. Where an individual had more than one number during his period of service, the number relevant to service in Korea is displayed. Where an individual served in more than one branch of the armed forces, a record will be displayed for each period of service. |

Date of Birth |

The date recorded on the service record as the date of birth. |

Place of Birth |

The place recorded on the service record as the place of birth. |

Dates of Service |

The dates an individual was allotted for duty in Korea or commenced duty in the defined operational area of Korea through to the last date an individual served in the defined area of Korea. |

Date of Death |

Indicates the date of death while serving in the defined operational area or a later date of death attributed to that service and occurring during the period covered by the Nominal Roll. |

Rank |

The substantive rank (excludes brevet, honorary, acting or temporary) held by the individual on either their last day or date of death in the operational area. |

Branch / Corps / Mustering |

These are service specific terms that denote an individual's function or speciality within their chosen service. Traditionally the "Corps" system used by the Army is quite broad in the way it groups functions together when compared to the "Mustering" system used by the Royal Australian Air Force, with the "Branch" system used by the Royal Australian Navy falling somewhere in between. |

Honours |

Indicates any Imperial or Australian honours and awards conferred on an individual during the Korean War. Service or campaign medals are not recorded. Foreign honours and awards are also not recorded. The issuing of honours and awards and service and campaign medals is the responsibility of the Department of Defence. |

Prisoners of War |

Indicates whether the individual was a prisoner of war. |